1851-1930

Childhood and Youth

A real Normandy from Cotentin! strong physically and morally, gifted, thrifty, rich in practicality, calm, hard at work. Her name is Léopoldine-Marie-Céline Féron, and she was born on January 24, 1851 in Anneville-en-Saire. His father Ambroise-Auguste was a farmer and had married Cécile Énault, probably in Quettehou, near Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue. From this union were to be born seven children, four boys and three girls. Leopoldine was the second of this small tribe.

One of her relatives was a Carmelite in Valognes and it happened that in the family we were surprised by this contemplative vocation whose usefulness did not seem obvious. And Léopoldine, who since childhood had dreamed of being a nun, retorted: “Well! Me, despite everything they say, I will one day imitate my cousin.” The reading of the Lives of the Saints awakened in her heart such generous ardor that, without wasting time, she trained herself in martyrdom! She had a whole character and clashed with her mother with such energy and, at times, violence that her parents were sorry for her aggressive disobedience. But around eleven she became aware of her malice and began to correct herself. Temperament but a good background.

She entered the Pensionnat Notre-Dame de Saint-Pierre-Eglise, run by the canonesses of Saint Augustine of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame (the sisters of Notre-Dame). Léopoldine was very gifted for studies and her inquisitive mind would have served her if her desire to be a Carmelite and the fear of imposing an expense on her parents had not led her to interrupt her studies. “I only wanted to stay in class long enough to learn what it is essential to know in order to be self-sufficient in the community; how much I regretted it afterwards!”

His spiritual adviser, the “director of conscience” at the time, a former missionary who had been chaplain of the Carmel of Saigon, helped him a great deal in his vocation but directed him towards the Charterhouse. She stayed there for three weeks. Three weeks of tears. Really, that was not his way. On October 11 (or 13) 1871, Mother Geneviève de Sainte-Thérèse, none other than the foundress of the Carmel of Lisieux at the time prioress, opened the doors of her monastery to him. She was twenty and a half. “Was I lucky,” she said, “that the Carmel of Lisieux was exhausted by the foundations of Saigon and Caen! Without that I would never have been received there, especially as a choir sister, because my director did not want to propose me as a sister of the White Veil and I had to sacrifice my attractions. »

At Carmel

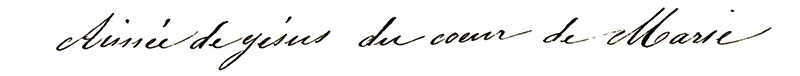

After a few months of postulancy, she took the habit on the feast day of Saint Joseph 1872 and received the name of Sister Aimée-de-Jésus du Coeur-de-Marie. On May 8, 1873, she made her profession at the same time as Sister Saint-Jean-Baptiste and the superior of the monastery, M. Delatroëtte, gave her the black veil and delivered the homily.

After her profession, she was given as an assistant to the first nurse, Sister Adelaide, and at the same time charged with the office of the relics. She thus learned to care for the sick, and displayed in this work an ingenuity and a charity that would later delight little Thérèse. This task often forced her to suppress her free time, where she would gladly have written to her family whom she loved so much. She suffered greatly from being cloistered in Lisieux when her loved ones faced illness: "If you only knew," she wrote to her sister Marie in September 1896, "how painful it is to be away from one's family at the time of the ordeal and of death, you would pity me a little. This cry is not a complaint but a regret. I still bless the good Lord through my tears."

Sr. Aimée maintains deep ties with the land, as can be seen on the occasion of the sending of fresh butter by her family. She describes to her sister Marie the joy of Mother Marie de Gonzague receiving such a gift: "If you had seen her tenderness when you received the little hamper, you would have enjoyed having taken the liberty of bringing into our Carmel a sweet and excellent messenger. I love everything that comes from my family and my country. In the season we are in, it is surprising that your butter is so firm and so delicate. All the sisters have made this remark: it is our dessert at the moment! (June 1899)... I recognized by the fine and delicate taste of the butter that the spring grass was purple" (May 1901).

She suffered from her summary education when she had to recite the Office in Latin, obviously without understanding the first word! She persevered and after years of effort, she penetrated the beauty of the liturgical texts and soon the breviary held no more secrets for her. No heading escaped her, but above all she savored the riches of the liturgical texts.

Accustomed to rough "useful" work, she had never been interested in the finesse of the needle and she suffered, in her youth, from finding herself so clumsy in the art of embroidery in which her novice colleagues excelled. His spirit of poverty was remarkable, his scrupulous obedience. People admired his humility and his fraternal charity. Sr Aimée cheerfully took on the heaviest tasks and what is remarkable, she never refused. no service, to the point that her sisters suspected her of having made a wish.

It seems that she had, however, a complex and difficult nature to grasp, with a modesty restraining her from expressing her feelings. "It's not easy to say all you want when you don't express your thoughts yourself," she wrote to her sister (May 9, 1900). Endowed with a great intelligence, she hid deep qualities of heart and a solid piety under a roughness of form which recalled her rural origins and disconcerted at first sight. Besides, she was meticulous, which could complicate the simple things.

We have retained a few testimonies from Carmelites who knew her well: “She was good, good, but she was a farmer, she had a complex, she was not up to it in this milieu. With Sister Marie du Sacré-Coeur she argued all the time. I understood why she didn't want Sister Geneviève. She was not comfortable with the Martin family. At graduation she came to talk in the kitchen with the sisters of the White Veil. There she was fine. Another defends her: “She relaxed and folded all the laundry while the others went to relax during the holidays! Ah! she did some work on her own for others. Another still: “Ah! This good Sister Aimée-de-Jésus, she earned merits in the attics watching the laundry in all weathers!”

We were amused by his sentences, so this one duly displayed "My habits are invariable and never change". But, as a nurse, it was in his arms that Mother Geneviève de Sainte-Thérèse died, who, having become blind, could not do without her charitable caregiver and it was to her that the venerable foundress confided a few minutes before her death: “ My sister Aimée, how one must suffer to die!”

In 1899, she was recalled to the infirmary; she was also in charge of various manual works, carpentry in particular which was remarkable at the time, but she particularly exercised her activity in the lingerie. She also took on the heavy lifting of the laundry, neglected by the elderly and often sick lay sisters, and she was constantly inventing techniques to improve her work.

With Therese

She had therefore been in the Carmel for more than sixteen years when Thérèse entered it in the spring of 1888. She herself admits that their relationship was not particularly intimate and that many things had escaped her. At the Trial, however, she declared: “What particularly struck me in the life of the Servant of God was her humility and her modesty. She knew how to go unnoticed and keep hidden the graces and gifts she received from God and which many, like me, only knew after her death (...) Sister Thérèse even as soon as she entered at age 15 [ to me] seemed very judicious and prudent in all things. There was nothing indiscreet in his way of practicing the virtues. She also evokes, speaking of Thérèse, her punctuality, her perfect serenity, her religious demeanor, and in her exterior, nothing childish or frivolous despite her young age, in such a way, she adds, that no one in the community thought of treating her like a child.

We know that Sister Aimée will be very opposed to Celine's entry into the Carmel. Not only because she apprehended, no doubt like several other sisters, the influence of four sisters united in such a small community, but also because she felt that Carmel did not need artists. It was only necessary to aim at the practical: to have good nurses, seamstresses, dressmakers. So, she wondered, why put flowers in the courtyard? Potatoes would be much more useful than the rosebushes that surround Calvary!

Thérèse was aware of Sister Aimée's opposition to Céline's entry, she recounts in the Story of a Soul (Manuscript A, folio 82 v°) she prayed like this: “You know, my God, how much I want to know if daddy has gone straight to heaven, I am not asking you to speak to me, but give me a sign. If my Sister Aimée-de-Jésus consents to Céline's entry or puts no obstacle to it, it will be the answer that Papa has gone straight with you. As soon as she left the chapel, Sr Aimée approached Thérèse and spoke to her about Céline, with tears in her eyes!

An incident was to break out later between Thérèse and Sister Aimée-de-Jésus, still about Céline who had become Sister Geneviève of Sainte-Thérèse. She could indeed be admitted to make profession from February 6, 1896 and therefore do so in the hands of Mother Agnès, whose priorate ended a few weeks later. Mother Marie de Gonzague decided to delay this profession, no doubt to help Céline distance herself from her family. Now, during recreation, Sister Aimée-de-Jésus, who was not aware of the details of this decision, declared outright: “Mother Marie de Gonzague has the right to test this novice like any other. It was then that Therese replied with emotion: "It is a kind of test that should not be given." This response astonished Sister Aimée, who took some time to understand that it emanated from a spirit of deep discernment more than from an overly natural affection. Relating this incident several years later, Sister Aimée added, speaking of Thérèse: “I am sure that she would have been an excellent Prioress, that she would have always acted with prudence and charity without ever abusing the right of authority. »

Sister Aimée left her job as a nurse at the start of Thérèse's illness. Only once could she approach her to help change her bed. It was Thérèse who suggested it: “I think my sister Aimée-de-Jésus would easily take me in her arms; she is tall and strong, and very gentle around the sick. » And during the Trial, Sister Aimée still remembered the heavenly gaze so full of gratitude and affection that Thérèse then gave her. She kept the memory of it as a pledge of her protection, and also as a consolation for having been the only one not to hear the bell of the infirmary which summoned the sisters at the time of Thérèse's death. She helped, however, soon after, to his burial.

After Teresa's death

Sr Aimée wrote to her family shortly afterwards: "I often think of death. This is not surprising. The memory of our dear Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus who died on September 30 at the age of 24, the Father Youf's departure to heaven 15 days later have not been erased from my memory. Death visits us quite often in the space of a year, three premature deaths, so to speak: a young tourière aged 36 [Sr Marie Antoinette], the youngest of our sisters [Thérèse], and the chaplain who was only about fifty years old."

Sr Aimée is happy to send a copy of theStory of a Soul to her family: "A treasure, she wrote to her sister Marie: you will read, you will understand, you will know how to appreciate it... it will be a pleasant surprise." Sr Aimée even sends her flyers soon after "to make known the book of my sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus by going to the market in Barfleur or St Vaast, and if you can give some to the booksellers, you will make us happy , however without making an express trip." But when it came to the beatification of Thérèse, Sister Aimée-de-Jésus was shocked. Think of Mother Geneviève, the venerated foundress, but Thérèse, who did nothing extraordinary! “It's at the instigation of his sisters that we owe this, don't doubt it... Let's wait! the truth will certainly come to light. This restraint earned her to be called as a witness at the Beatification Process, the Promoter of the Faith (Mgr Verde, the devil's advocate) having asked her to hear another story about Therese!

She quickly changed her mind, and her great joy during the last twenty years of her life was to work in the service of the nascent pilgrimage and to hear daily, in the mail received from all over the world, of "her Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus”.

September 30, 1922 was a great day for her and for Carmel. We were celebrating, in anticipation because of the upcoming feasts of the Beatification of Thérèse, her own golden jubilee. The ceremony was presided over by Monsignor Lemonnier, who spent long hours at the monastery. Monsignor blessed the statue of Thérèse at the entrance to the courtyard, a room of relics was inaugurated at the end (known as the Magnificat) and the next day, the novices interpreted in honor of the jubilee a piece they had composed: "La leafless rose", where we saw Thérèse preparing one of her most beautiful roses for Sister Aimée.

But the years were inexorably added to the years. She became deaf. Cruel ordeal for her to no longer be able to hear the liturgical chants! One night in September 1925, she heard a delightful concert. Surprised she looked in the night and saw no one. The event was repeated the next day and she saw in it a delicacy of Therese.

In 1927, a carbuncle severely affected her health and she had to undergo several surgeries. She suffered a lot but she offered her sufferings so that the resources necessary for the construction of the Basilica would not be lacking. However, she recovered from this serious health problem, aggravated some time later by pneumonia. Restored, she resumed her work with her usual energy.

It seems that during her last years she was favored with special graces from Thérèse. Age however was there, she gradually lost her sight, which deprived her almost completely of the divine office she loved so much. She even had to give up going to the refectory, the day she felt a violent pain in the shoulder and the right side. She then had no illusions about her approaching end. The doctor called diagnosed a double pneumonia. Very weakened, she was heard to murmur: "... the grace of a holy death... through the intercession of our little Saint Thérèse..." She fell asleep peacefully on January 7, 1930 at 3 a.m. Morning.

P. Gires