The Story of a Soul 1898 team

Bottom left to right: Marie, Céline, Mother Agnès (Pauline) and cousin Marie Guérin.

The genesis of this book, promised to a fabulous destiny, begins in sadness, when there is talk of the imminent death of the very young Sister Thérèse, at the Carmel of Lisieux. When a Carmelite dies, her sisters usually write a short biography for the other Carmels. It briefly recounts his childhood, his desire for Carmel then his entrance, the different stages of his religious life, the services rendered to the community and finally, his illness and his death. In the community, this document is called a circular because it "circulates" so to speak in the monasteries, although each receives its own copy.

In Lisieux around the middle of 1897, Thérèse's relatives knew that she was soon to die. Her sister Pauline (Mother Agnès) is already concerned about writing her circular. Indeed, how to write the circular of a Carmelite who is only 24 years old and has so few achievements to her credit? Mother Agnès reflected on this especially since May 30, 1897. Shortly before, Thérèse had asked Prioress Marie de Gonzague (photo opposite) permission to entrust her sister with the well-kept secret of her first hemoptysis in April 1896, and she did so on May 30. Mother Agnès listens to her, concluding that the disease is very advanced, much more than she thought. Tuberculosis did not start just a few months ago, but it is already very old. In general, people affected do not survive more than two years.

For the circular itself, Mother Agnès thought of using the childhood memories recounted in 1895 by Thérèse in what would later become Manuscript A, but as there is little in this text about her religious life, she would like a suite. She misses the family celebration of May 30 around the taking of the veil of her cousin Marie Guérin and on the night of June 2, she will discuss her project with the prioress Marie de Gonzague. The latter finds the idea very interesting and asks Thérèse to continue writing, this time about her religious life.

The next day, that is from June 4, Thérèse ceased all activity to write only her "little homework" (CJ 25.6.2). The young Carmelite woman writes with great difficulty in a black notebook what will become Manuscript C. The task is painful but Thérèse is aware that her text will be published, that it will be part of her circular. We talk to him about an integration with his first text. Will she give some ideas for this edition? Perhaps, because she reread the text of the manuscript she wrote in 1895 and admits to being very moved by it (see August 1, 1897). She trusted her sisters, and especially Mother Agnès. To get an idea of the result, here is a copy of the beginning of the publication, alongside Therese's original. To read the entire text presented in synopsis, see Story of a Soul.

In Lisieux around the middle of 1897, Thérèse's relatives knew that she was soon to die. Her sister Pauline (Mother Agnès) is already concerned about writing her circular. Indeed, how to write the circular of a Carmelite who is only 24 years old and has so few achievements to her credit? Mother Agnès reflected on this especially since May 30, 1897. Shortly before, Thérèse had asked Prioress Marie de Gonzague (photo opposite) permission to entrust her sister with the well-kept secret of her first hemoptysis in April 1896, and she did so on May 30. Mother Agnès listens to her, concluding that the disease is very advanced, much more than she thought. Tuberculosis did not start just a few months ago, but it is already very old. In general, people affected do not survive more than two years.

Text of the Story of a soul of 1898

additions are in blue

Before taking up the pen, I knelt in front of the statue of Mary [This precious Virgin, although without any artistic value, was twice animated to enlighten and console, in serious circumstances, the mother of our angelic child. She herself received signal graces from this blessed statue, as we will see later.] : the one who gave to my family so many proofs of the maternal preferences of the Queen of Heaven, I begged her to guide my hand, so as not to draw a single line that would not please her. Then, opening the holy Gospel, my eyes fell on these words: “Jesus, having gone up on a mountain, called to him those whom he pleased. This is indeed the mystery of my vocation, of my entire life; and above all the mystery of the privileges of Jesus over my soul. He does not call those who are worthy, but those whom he pleases. As Saint Paul says: “God has mercy on whom he wills, and he has mercy on whom he wills to have mercy. It is therefore not the work of the one who wants, nor of the one who runs, but of God who shows mercy. »

For a long time I wondered why the good Lord had preferences, why all souls did not receive an equal QUOTE of thanks. I was surprised to see it lavish extraordinary favors...

Original text by Thérèse published in 1956

deletions are in black

Before taking up the pen, I knelt down in front of the statue of Mary (the one who we gave so many proofs of the Queen of Heaven's motherly preferences for our family), I begged her to guide my hand so that I did not draw a single line that was not pleasing to her. Then opening the Holy Gospel, my eyes fell on these words: “Jesus having gone up on a mountain, he called to Him those whom he pleased; and they came to Him. (St. Mark, Chap. III, v. 13). This is indeed the mystery of my vocation, of my whole life and above all the mystery of the privileges of Jesus over my soul... He does not call those who are worthy of them, but those whom he pleases or as St. Paul: “God has mercy on whom He wills and He has mercy on whom He wills to have mercy. It is therefore not the work of the one who wills nor of the one who runs, but of God who shows mercy. » (Ep. to Rom. chap. IX, verses 15 and 16).

For a long time I wondered why the good Lord had preferences, why all souls did not receive an equal degree thank you, I was surprised seeing him lavish extraordinary favors...

An editorial continent

And so the texts are reviewed and put together once the little black notebook is finished. We begin by imagining that they are addressed to the same person, namely Marie de Gonzague the prioress - a maneuver which will make Thérèse's text more easily accepted by the Carmels for which it is above all intended. Indeed, if the prioress authorized it, it does not seem strange for a nun to write her memoirs in this way. We add some elements to make it easier to read. Then the manuscript was enriched with letters, for example those addressed to Bellière. Mother Marie de Gonzague assumed responsibility for the project and already spoke about it to Father Bellière in August 1897, then to Father Roulland in November 1897. We also think of inserting in the large manuscript of this "circular" letters from Thérèse to Marie du Sacré-Coeur, which will later constitute the Manuscript B. The sisters then add excerpts from Thérèse's letters, some fifty of her poems, four of her prayers and passages from her Pious Recreations. The young people write down their memories of Thérèse as mistress of novices. We add a selection of the last interviews and finally, the story of Thérèse's death.

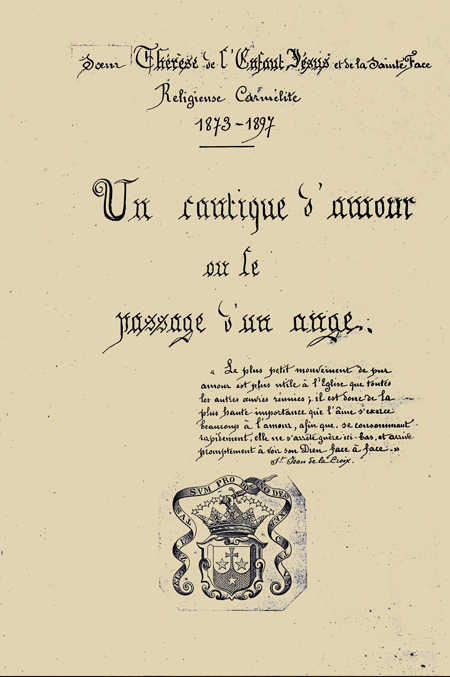

All this set will be shaped into 12 chapters and the book in the making bears a title: A canticle of love or the passage of an angel. Marie de Gonzague prepares a Preface towards the end of 1897, where she explains that this precious manuscript - written by a "diamond", a "star", a "flame!" - had to be given to the world. Read this Preface here.

As it greatly exceeds the usual size of a circular - three pages - Marie de Gonzague thinks of seeking advice. This circular has indeed become a book. Superior Alexandre Maupas gave her permission in October 1898, but to reread and possibly correct the manuscript, the prioress turned to the Mondaye Fathers who had the full confidence of the Carmelites. You can read his letter of 29th October, 1897. Godefroid Madelaine accepts, quickly edified by the quality of the text. He began work on the manuscript at the very beginning of 1898, and in March he finished, having done a lot ofobservations. He suggests many omissions, especially in intimate details, but years later he would apologize to the sisters for his "blue pencil that made you jump to the ceiling!" His colleague Fr. Norbert Paysan corrects the poems. In April, Fr. Madeleine composes a letter of introduction which will be inserted at the beginning of the book.

There remains one step before publishing: obtain the authorization of the local bishop. It is then, Mr. Hugonin, the bishop of Thérèse, the one from whom she had asked permission to enter the Carmel at the age of 15. In 1898, he was 74 years old and very ill. Fr. Madelaine will meet him on March 7, shortly before his death which will occur at the beginning of May, and he obtains an oral agreement for the printing permit (imprimatur). We have kept a written record of this meeting, via Fr. Madelaine. These are the few words in purple ink on the right side of this 20 cm piece of paper. by 7 cm., authenticated in 1909 by Mother Marie-Ange at the mine in the left section (which however only entered in 1902...).

In April 1898, the book got its definitive title, from a letter from Godefroid Madelaine to Marie de Gonzague: Story of a soul written by itself. The success of all her steps will long delight Marie de Gonzague, who took an important part in the preparation of the text and who wrote with pride in 1904 having got publication of this manuscript. [letter to Fr. Tessier].

Looking for a printer

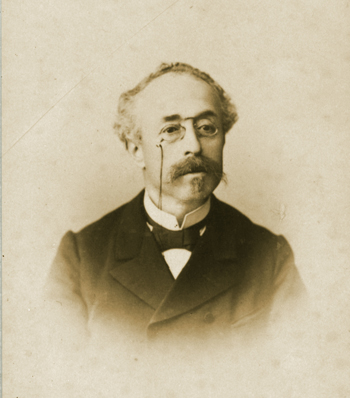

All that remains is to print. This step was then very complex, because it was first necessary to have the text typed. It is necessary to find some printer-typographer who does not charge too much because the circulars are automatically sent to the other Carmels, they are not sold! For this future book whose manuscript already contains a few hundred pages, we turn to Uncle Guérin (photo below left). It is usually he who helps out the Carmelites with his largesse. He agrees to have this book written by his niece printed, and he immediately gets quotes from several publishers-printers.

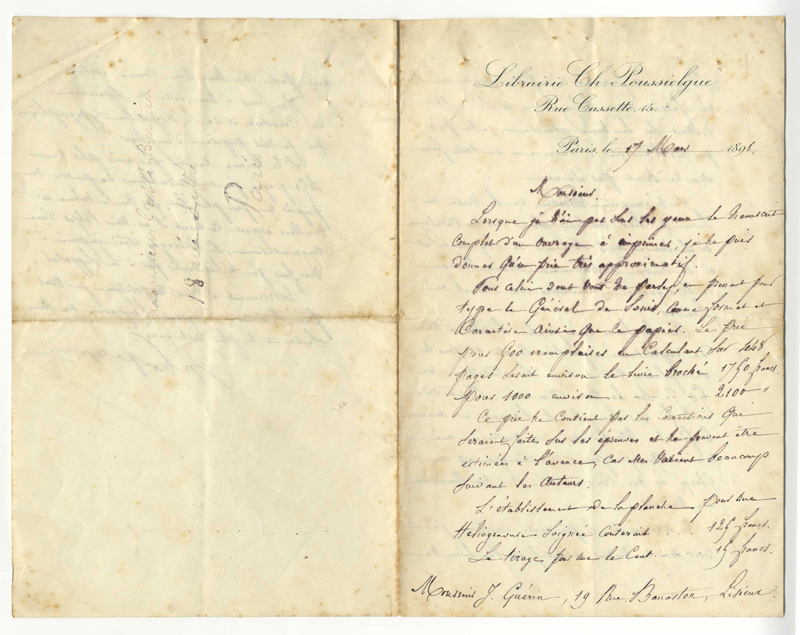

Isidore begins by writing to the Librairie POUSSIELGUE rue Cassette in Paris, which replies to him on March 17, 1898: The price for 500 copies, calculated on 448 pages, would be around 1750 francs for a paperback, for 1000 around 2100 francs. Mr. Poussielgue also discusses the quality of paper, photos to insert. He could distribute the book himself, and grants a discount to priests and religious communities. This letter is interesting because it is the first that Mr. Guérin receives, and he will use it to evaluate the other quotes.

Then follow two negative responses from La Croix, written on March 26 and 30, suggesting other printers without offering prices.

Le April 7th, Marie Guérin asks her mother if her father will choose Poussielgue, specifying that it is Pauline who is worried. Papa's or Mama's answer is probably given in the visiting room, because we don't have a written text.

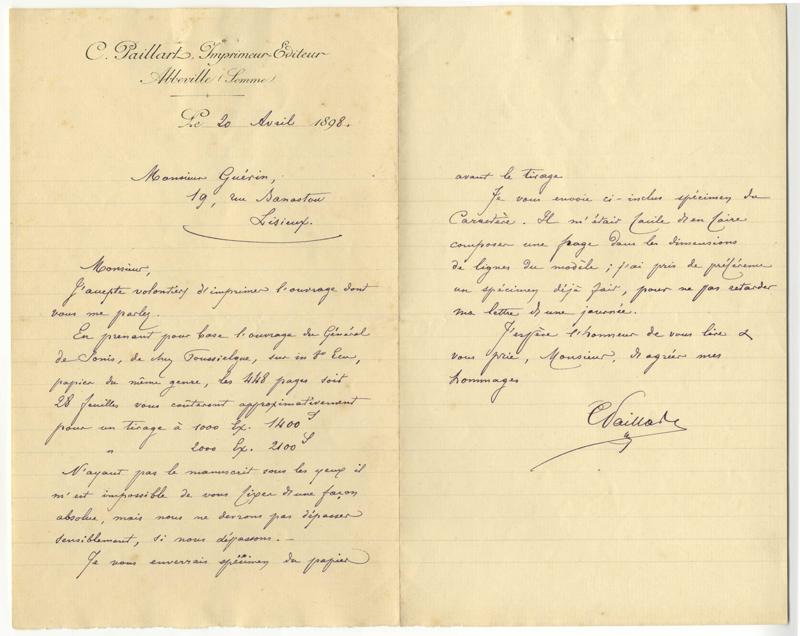

But Isidore has turned to other printers and is already receiving responses. PAILLART, from Abbeville, wrote to him on April 20, proposing a print run of 1000 copies at 1400 fr., and 2000 copies. at 2100 fr.

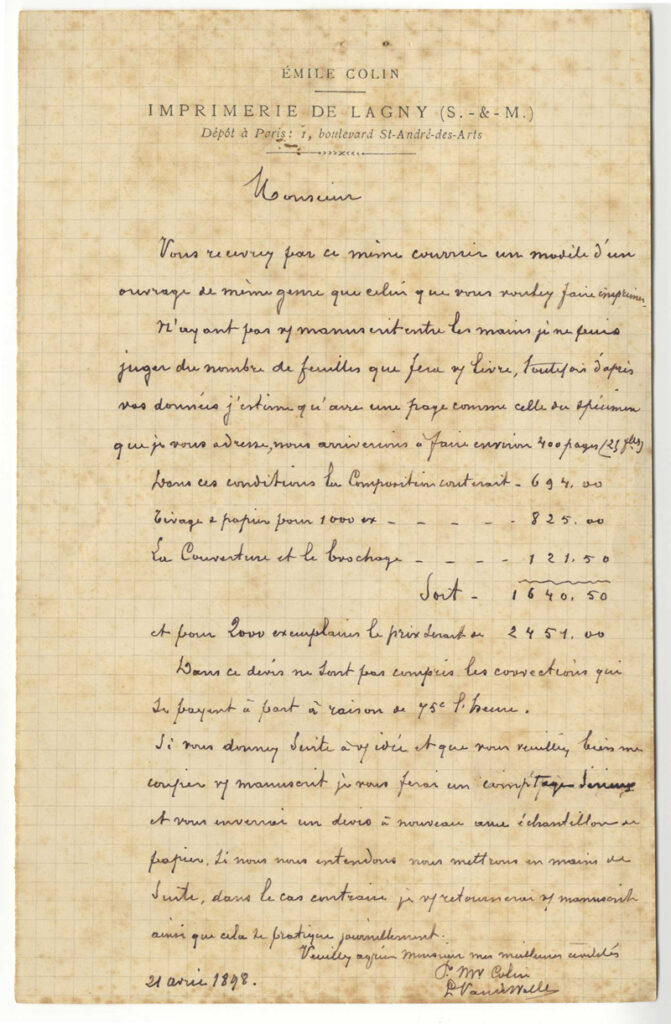

Then it is the turn of EMILE COLIN who, for approximately 400 pages, offers the print and the paper in more detail, plus the cover and binding of 1000 copies at 1640,50 francs, including the composition. For 2000 copies the price would be 2451,00 francs.

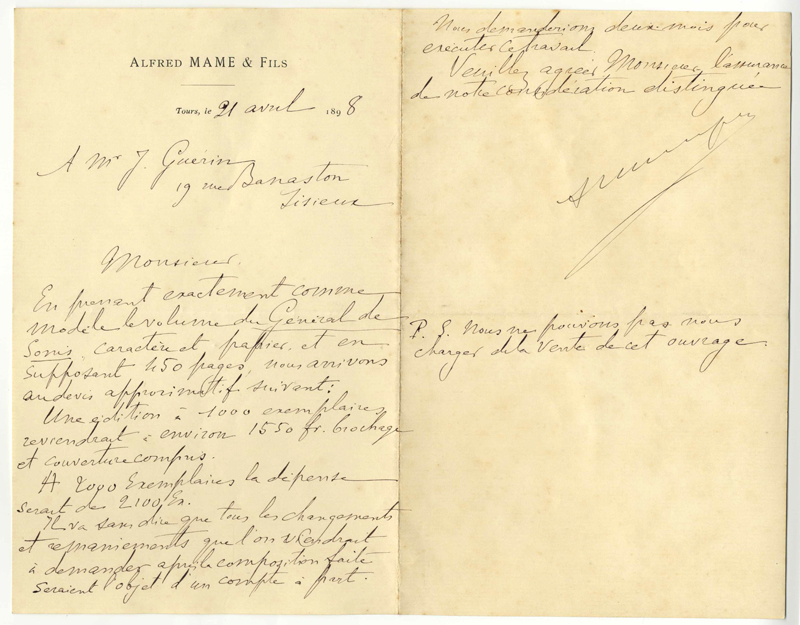

Alfred MAME & FILS replied the same day, April 21, that 1000 copies of 450 pages would cost around 1550 francs, binding and cover included, and 2000 to 2100 francs. And the next day, April 22, the NOTRE-DAME DES PRÉS printers in Montreuil-s-mer replied, unable to do the job but suggesting another printer, whose prices are provided: 450 pages in 1000 paperback copies under color cover at 1500 francs , and 2000 to 2000 francs. We also offer a superior quality paper, with prices of 1660 fr for 1000 copies, and 2342 fr for 2000.

Between all these answers, Mr. Guérin also receives an estimate of the work of Saint-Paul, not preserved. With all these estimates, he consults someone who knows about printing, Father Marie des Augustins de l'Assomption, whom he met in Lourdes during a pilgrimage. The latter responds to mine on May 12:

You must find me very negligent. But my poor hand has not allowed me all these days to hold a pen - So please don't blame me. L'Oeuvre St Paul has become a serious house – it is starting to do well – it cannot be compared to Poussielgue and Retaux. She works as well as Paillart...

We understand that St-Paul cannot yet do as well as Poussielgue and Retaux, but would compete well with Paillart. But Paillart and Mame are at the same price, ie 2000 copies for 2100 francs. It is possible to deduce that St-Paul is less expensive and that is why Mr. Guérin questioned Father Marie. Mr. Guérin will follow the advice of this man, and it is the Work of Saint-Paul which will win his support. This house was created in 1873 to work for the defense and propagation of Catholic truth through inexpensive typography. The estimate of St-Paul has not been preserved, but we sign for 2000 copies, in two draws of 1000.

Also in May, Mr. Guérin contacted another bookseller-publisher, considering depositing the book in Paris. On May 18, Victor Retaux, Bookseller-Publisher of Paris, writes a negative answer to this request for deposit, declaring that "The new Constitution of the Index does not allow me to publish a work of the kind of the one whose deposit, if I have not previously obtained the authorization of the Ordinary. So please send me the complete proofs of the book. I will submit them to His Eminence Cardinal Richard and if, as I hope, he gives me the imprimatur, we will easily agree on the terms of sale. Which suggests that the imprimatur transcribed by Father Godefroid Madeleine would not be sufficient to print in Paris? But Victor Retaux pulls himself together and writes again on May 1, 25 and declares, while including his prices for a deposit of a book: "I believe that the reasoned Approval of Mgr Hugonin will suffice."

The manuscript is given to St Paul for typesetting. According to an oral tradition collected by a sister from La Pommeraye in 1987, a typographer from Bar-le-Duc who was working on Thérèse's manuscript copied sentences from his daily work and made his family pray with these extracts on returning home. him! This stage of composition seemed long because in July, Marie Guérin complained to her parents: "Has Dad received any news from the Librairie St Paul? It's starting to be a little known." And she continues: “Finally, we have to hope that they will put their efforts there, at the Bookstore!” (before July 16, 1898).

A few more pictures

We are also thinking of putting some pictures in the book. In particular, there will be on the frontispiece the photo no. 37 of Thérèse, opposite on the right. It will be reversed during editing. It is Madame Besnier, photographer in Lisieux, who prepares the heliogravures. And she does it very well, according to Marie Guérin: "Mme Besnier has just sent her proofs. They are perfect, very well done, there was a certain small defect and so we asked her to come to Carmel to give her our explanation. She understood very well and was very kind, and so were we. The test is very gentle, there was one that was a little sad expression, but Mrs. Besnier guessed what did that was because she was a little less black than the other. Our Mother has been in the visiting room and finds Mme Besnier very well, her little daughter was there too and our Mother gave her a present of a little lyre, you know, like I had one in my room. My Sr. Geneviève had a lot of explanations about photography. Mrs. Besnier will send her all her processes, all her formulas for toning and glossing. She gave her showed her painting in a photograph, she perfectly recognized my Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus and asked for a photog raphied as a great favour. She told us about this that she had kept all our family photos since our childhood. Madame Besnier left Carmel delighted. So here is a big thorn from the foot: successful photography." (letter of July 1898)

The imposed deadline is used to add text to the manuscript! And yes, Marie de Gonzague, in this same letter of July 1898, asks Uncle Guérin to add more poetry, which the community particularly likes. In we speak of the book as La Vie of Therese.

Finally, July 17, 1898 the first trials are received at Carmel. It was about time as news of the impending release is starting to spread around town. Mr. Guérin will soon talk to the Pottiers about it, as his daughter testifies: "I am very happy that Dad told you the little secret about the life of our dear little saint, I wanted to tell you a long time ago. TO DO!" (September 1898)

The corrections are first made in community, then the proofs are sent to Isidore early September: sewn, for those that have only been checked once, and detached for the others. And we discuss choice of paper with the family: too thick, too beautiful?... while Mr. Guérin regularly sends pages to St-Paul with his good for shooting (August 22, 1898). Mother Agnès intervenes, we do not know why, directly with the printer, which offends Mr. Guérin but we seem to be quickly reconciled (letter from Marie at the end of August 1898).

And in September, we are just waiting for the book: "When mom comes, writes Marie Guérin the 26, let her bring or send the first six leaves drawn from Life!" The long-awaited book was undoubtedly promised for the end of September.

However, in all the traces written on this September 30, 1898, the first anniversary of Thérèse's death, there is no mention of the arrival of the book. Marie Guérin writes to her parents at all beginning of october, recounting the day of the 30th, without a word about the book. Finally, it will not be released until October 21 (according to a note from Celine on a loose leaf undated – pre-1905). Let us add that the first reactions of readers are dated October 22, 1898, which confirms this choice. You can read these here.

It so happened that the manager of the Saint-Paul printing office in Bar-le-Duc was at the Oeuvre's bookshop, rue Cassette, the day the book came out. She remembers the sale of the very first copy to a priest, who hesitated to take it for another person, sick. But after reading the book, this person obtained his healing through the intercession of Sr Thérèse! Happy starting point of the dear volume (cf. Annals Nov. 1935).

We immediately sent them to the 121 Carmels in France and 18 foreign Carmels, with a note from Marie de Gonzague encouraging the distribution of the book. How she will be obeyed! We will immediately withdraw the second thousand, and in May 1899 the second edition will be ready.

The book is on sale at 4 francs.